Jules de Palm: The Dutch West-Indian Man

by Blake Sonnenfeld

A mention of Jules de Palm as a great figure in Dutch-Caribbean literature is to underrate his almost hundred-year long life. To a great extent, De Palm personified the Dutch West-Indian colonial history. His literary links featured heavily on topics in Aruba, and Curaçao. His approach to Caribbean literature was undeniably transformational in its scope, but more so in its tendency of speaking directly to social consequences of colonial history through its characters, and in multiple Dutch colonial contexts.

This article discusses De Palm’s plethora of contributions which make him a man of great stature not only in the literary sense, but also in the cultural sense in the context of Dutch colonial history in the 20th Century.

Jules de Palm was born on 25th of January, 1922 in the Colony of Curaco in the Dutch Antilles. His first public contribution as a thinker on pan-Caribbean questions that related to society appeared on 9th July, 1942 in ‘Jong Suriname’. This was the newspaper of the JFP, the organization that represented Surinamers in Curaçao. His article was titled ‘Hoe ik mij Suriname voorstel’ and it directly addressed the phenomenon of Surinamese economic migration to Curaçao. The article portrays a point of social contention in the context of pan-colonial relations. De Palm offers a praxis picture of how tensions between people that are put in competition with each other manifest in Curaçao. De Palm reflects on his perceptions of Surinamese guest workers in Curaçao, and displays the cross section between his conceptions, and his view of his conceptions.

The article is representative of his rich use of irony, a trait which came to define his approach to topics and writing style. De Palm uses this irony to address what he perceives as oxymoronic attitudes in Surinamers in Curaçao. He describes first his impression and how Surinamers themselves speak about their country4:

“een land met ‘vreselijk knappe mensen’, ‘malaria’, ‘bosnegers’ en ‘takkitakki’.”

And also how Surinamers:

“in gloedvolle woorden spreken over hun vaderland”.

However, at the same time, De Palm maintains:

“Elke keer als ik het voorrecht heb een Surinamer te spreken, wordt mij eerst duidelijk hoe pover en armzalig mijn geliefd vaderland is. Het ‘bij ons in Suriname’ ligt a.h.w. bestorven op de lippen der bewoners en wordt gebruikt om in ’t oog te doen springen hoe gebrekkig en onvolmaakt Curaçao is, dat met open armen de ‘verlichtende geesten’ ontvangt die het zullen opheffen uit de duisternis waarin het gedompeld is.”

De Palm also lauds the level of education in Suriname, commenting: “Geen land met een groter percentage intellectuelen”. However, the compliments serve as a way to maneuver to his ironic series of comments that show his irritation as the condescending attitude of Surinamers in Curaçao.

“Vurig verlang ik naar ’t ogenblik dat ik voet aan wal kan zetten om dit nimmer genoeg te prijzen land, dat op de ganse wereld zijn weerga niet heeft, in ogenschouw te kunnen nemen.”4

This perspective of rivalry between Curaçaoers of which De Palm is one, and Surinamese guestworkers could be regarded as a treaty on a specific social phenomenon in the Dutch West Indian colonies. In a 20th century colonial context, people often found themselves in direct economic competition with each other. Furthermore, each of the colonies in the kingdom of the Dutch West Indies, also had to maintain the interests of its own considerations in the relationship between itself and the ‘fatherland’. In daily life, conflicts occur that reflect the individual and his struggle against an inferiority complex. De Palm displays here not only an astute eye for social matters, but his unique approach that would come to define his lifetime of authorship.

The Young Writer

After graduating as a teacher in Curaçao in 1942, Jules de Palm moved to the nearby Dutch colony of Aruba. He worked as a teacher at the Bernard School in San Nicolas until 1948. During his stay in Aruba, De Palm forged a lifelong friendship with Cornelius Albert Eman. Eman was the son of politician Henny Eman, who had formed the Aruban People’s Party (AVP) in 1942. De Palm was himself politically active for the duration of his life. In Curaçao he was a founding member of the Centraal Bureau Toezicht Curaçaose Bursalen (CBTCB) which brought writing fellows on the island of Curaçao together. From 1959 until his retirement in 1982, he served as Chairman of the CBTCB.

His notoriety in the Netherlands came about from his time studying at the School for Language and Literature in The Hague and at the university in Leiden. He was awarded a doctorate in Dutch Language and Literature in 1969.

The Three Language Renaissance and Pioneering Papiamentu

Jules de Palm as a teacher, writer, and thinker, not only contributed to each of these fields individually, but also had an enormous influence on the cultural development and consciousness of people in the Dutch West-Indies. As an educator from his time period in colonial history, De Palm was aware of the role that ‘Standard Civilized Dutch’ (ABN) played as the language of instruction in Curaçao and Aruba. He personally embraced the use of Dutch, but positioned himself in opposition to Spanish dominance brought in on the island of Aruba by Dominicans and people from Venezuela.

He found his vehicle to combat this through is role as Advisory Board member of Sticusa. This was a Dutch organization that from 1948 until 1991 was tasked by the Dutch government to stimulate cultural collaboration between its Eastern and Western colonies. During the period when De Palm served as Advisory Board member, he spear-headed artistic exchange between the Netherlands, Suriname and the Dutch Antilles. Sticusa is an antonym that during the organization’s existence from 1941 to 1991 had different meanings. De Palm served as Deputy Chairman of Sticusa1. De Palm’s participation in the organization took place in the early 1970s. This was after the cultural and political break in the organization with Indonesia in 1955, a change which saw the organization reform as Nederlandse Stichting voor Culturele Samenwerking met Suriname en de Nederlandse Antillen and saw the organization take on a different form as cultural equal with the Netherlands in the organization’s governing statute.

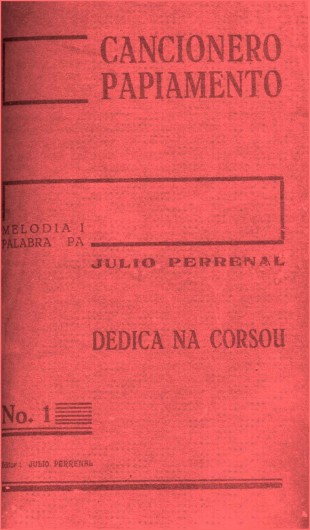

De Palm’s first move in the direction of the Papiamentu renaissance in art that he is now widely known for, came in 1943. Writing under the pseudonym ‘Julio Perrenal’, De Palm collaborated with contemporaries Pierre Lauffer and Rene de Rooy to write a series of ten songs in Papiamentu. This series of songs addresses the theme of modernization in Antillian society after the Second World War. The presence of a large number of American military personnel, as was the case both in British and Dutch colonies during the war, were in a large part a symbol of the changes taking place for the people of the Dutch Antilles at this time, both economically and socially. An aspect of this was the expression of folk pleasure and revelry in the songs.

The songs from ‘Perrenal’ reflect De Palm’s stature as a Caribbean poet. Furthermore, the songs are a valuable contribution to the phenomenon of calypso in 20th Century Antillian life. Calypso was originally a musical movement that started in Trinidad and Tobago. The discovery of oil on the islands near Venezuela meant that steel drums were left over after shipping. It was from banging on these steel drums that calypso began. Thematically, calypso as a subculture often addresses taboo topics in traditionally conservative Caribbean societies. The text of some of calypo’s most famous hits contain veiled sexual euphemisms and also express things that affect Caribbean society, but do not enjoy other public spaces for discussion. Double-meaning is another motif that is inseparable from calypso as a genre.

The contribution to the cannon of calypso from Perrenal is called Cancionero Papiamentu No. 1 and vibrantly reflects the genre’s soul4:

Ta kiko lo mi hasi

ku mi pushi sin manera

pasobra di mi pushi

tur kos lo mi por spera

[…]

E ta risibi bishita

tur anochi riba dak

no tin moda pa nan kita

i mi nervionan ta krak

[…]

These lines were translated into Dutch by De Palm as:

Wat zal ik doen

met mijn ongemanierde poes

want van mijn poes

kan ik alles verwachten

[…]

Zij ontvangt iedere nacht

bezoek op het dak

ze willen maar niet weggaan

en ik krijg er de zenuwen van

[…]

The songs were written in Papiamentu as a plea for the language not to be considered as a symbol of inadequacy and at the same time through the songs to stimulate social change regarding the perception of Papiamentu as a low-status vernacular. He expressed his plea “dat muziekgezelschappen – bestaande uit Curaçaoënaars – botweg zouden weigeren om in hun eigen taal te zingen…”

However, unfortunately enough, the reason for his plea became self-evident. On 7th of July, 1943, a number of musicians did not show up for the Curcom broadcast of Cancionero Papiamentu No. 1. De Palm had to perform himself in place of the other musicians. The ironic approach that De Palm is so renowned for in his writing seemed to manifest itself here in his actual life. As it relates to this attempt to elevate Papiamentu, it must have been a bitter affirmation for De Palm that the use of the language carried shame. In his attempt to elevate Papiamentu, it was shown just how severe the stigma of creating art in a vernacular was at this time. De Palm’s actions during this time reflect his role not only as a cultural thinker and active citizen, but also reflect his status as a pioneer of Papiamentu and Antillean cultural matters in general.

Next to his function as Chairman of Sticusa, De Palm was also a contributor to various series of works that the organization produced. He describes in the passage below, how two of these works ‘De kerstcakes van Shon Keta’ and ‘Shòròmbu’ were produced at the behest of Cola Debrot:

“Toen Debrot in 1954 een belofte aan Sticusa had gedaan om twee verhalen te leveren voor het jaarboek en die wegens tijdnood niet kon nakomen, droeg hij mij min of meer op zijn taak over te nemen. Ik voelde mij zo vereerd door het feit dat de schrijver van Mijn zuster de negerin mij in staat achtte hem te vervangen, dat ik onmiddellijk in de pen klom en ‘De kerstcakes van Shon Keta’ en ‘Shòròmbu’, na eindeloos schaven, persklaar maakte. Zijn waardering voor het eerste verhaal toonde hij door het in extenso over te nemen in zijn exposé over de literatuur in de Nederlandse Antillen (Antilliaanse Cahiers, 1e jaargang, No. 1, juli 1955).” [De Palm 1981: 103/104]

De Palm was a lifelong advocate for the development of Caribbean literature as a medium to bring attention to aspects of daily life for people in the Antilles. The two works that he produced for Sticusa are written as thematic inversions of each other and in doing so complement each other in their focus on social circumstances. The works display their commonality in how pronounced De Palm’s use of irony is in what are seemingly banal daily realities of life in the Curacies context. Both works were also later published in De Palm’s first short-story collection Antiya in 1981.

Kinderen van de fraters (1986)

Kinderen van de fraters is told through the perspective of a boy from the time of his enrollment in pre-school up until his time at Saint Thomas Collge in Curaçao. At the beginning the story, De Palm crafts and maintains the child-voice of the protagonist. As the story progresses, the child’s tone develops with his age as he moves to higher levels of education and experiences the increasingly complex interactions that come with coming of age. A number of elements come from De Palm’s contribution to broadcast storytelling through the ‘Wereldomroep’.

A central theme from the work is the distance between older generations of Curaçaoans, namely between the protagonist’s grandmother’s generation, and that of his mother. The novel’s first chapter present contrasting views of colorism. How the women have differing views of colorism is offered as possible evidence for the protagonist’s oppression at the missionary school. De Palm approaches this theme from the first page of the novel:

“Vooral omdat mijn ouders vonden dat een kleurling op Curaçao zich nederig behoorde te gedragen, genoot ik van het ‘vergrijp’ van oma die, volgens mij, helemaal geen reden had om zo uit de hoogte te doen…”2

A Caribbean child during this time period had to go to a missionary school in order to have a chance at an education that was empowering enough for social mobility. Furthermore, the protagonist’s ability to behave “as the whites can behave” is a definitive criterion that will influence his future opportunities for social mobility. The protagonist’s mother seeks things in her own child that will differentiate him from the other children which she describes as inadequate, and children that her son is too good to associate with. Whenever the protagonist brings friends home, his mother is always standing at the door to carry out her inquisition:

“Waar hij woonde, wie zijn ouders waren, wat zijn vader voor de kost deed, of zijn moeder wel met zijn vader was getrouwd, of hij soms familie was van die zuiplap die ’s zaterdags de hele stad op stelten zette.” 2

The protagonist also displays from the outset of the novel, a feeling of inferiority as it relates to his father. He compares the image he has of his own father with those of the white children who he views as more loving.

As the protagonist ages, the novel also addresses some of the more austere aspects of his experience in the missionary school. The topic of punitive action appears often in the novel as one of the central lenses of the protagonist. He describes often and in detail entire scenes of how punishment is carried out against the students by the priests. These descriptions make clear to the reader the trauma of punishment in a missionary school in Curaçao in the early 20th Century.

The motif from punishment creates a contrast between the conscious cheekiness of the protagonist as a child, but also the tragically comedic realities of his journey from childhood to maturity. The novel is ripe with the protagonist’s experiences with misunderstanding, misbehaving and the occasional unkind occurrence:

Henkla, henkla, frole bazòn

Henkla, henkla, frole bazòn

Mi n′ bisa henkla, mi n′ bisa henkla

Mi n′ bisa henkla si mi n′ ta mazòn.

Jaren later hoorde ik in Leiden, toen ik in het speelkwartier langs een kleuterschool liep, de kinderen zingen:

Hinkelen, hinkelen, vrolijk in ′t rond

Hinkelen, hinkelen, vrolijk in ′t rond

In Kinderen van de fraters, it is clear that De Palm wants to depict the youthful traits of naivety and innocence. An example of this is the focus he places on the societal role of superstition. The protagonist shows himself to be enthusiastic about African medicine women, who he admires as powerful based on books he has read at the missionary school. He notes as especially interesting that the power of the black medicine women is stronger than that of the white missionaries.

Lekker warm, lekker bruin; Vallen en opstaan in twee culturen (1990)

Lekker warm, lekker bruin; Vallen en opstaan in twee culturen appeared in 1990 as part of De Palm’s involvement with CBTCB. The contemporary Dutch writer, Jos de Roo, explains how De Palm places the theme of homesickness as central in the story. Homesickness amongst writers from the Dutch West-Indies occurs possibly in the same measure as the ‘good master’ in Caribbean post-colonial literary works. The homesickness is often portrayed through the lens of the author or protagonist spending time in the Netherlands for education or work. De Roo points out how the protagonist, Carlos, cries from loneliness and cites the poem ‘Rabia’ as an representative example of the homesickness that De Palm addresses.

Lekker warm, lekker bruin; Vallen en opstaan in twee culturen is approached somberly in comparison to other works where irony features more prominently. He also appears to consciously seek to bring the theme of Dutch ‘sombreness’ (‘de nederlands nuchterheid’) over to the reader by sharing things such as:

“Op wrede wijze is mij in Nederland geleerd dat ik me strikt aan de afgesproken tijd had te houden.”3

Conclusion

Jules de Palm was not only a witness to a hundred years of Antillean literature, but he was a participant in its broad renaissance along with contemporaries such as Pierre Lauffer and René de Rooy. That Papiamentu would be used as a medium for telling the stories of its people was given a precedence by how widely he sought to promote its use. An Aruban eulogy of De Palm speaks to his personal character as being immensely humorous, and he corroborates this through his writings. It aptly ends by sharing an adage:

Toen Jules 90 werd en ondergetekende hem meedeelde dat deze leeftijd niet niks was, antwoordde hij: “Ja maar Johan Heesters (een Nederlandse operazanger, AT) is 108 jaar geworden.”5

Bibliography

- Anton Korteweg, Kees Nieuwenhuijzen, Max Nord en Andries van der Wal (samenstelling), Schrijversprentenboek van de Nederlandse Antillen. Amsterdam: De Bezige Bij, 1980.

- De Palm, Jules, Kinderen van de fraters. Amsterdam: De Bezige Bij, 1986.

- De Palm, Jules, 1990. Lekker warm, lekker bruin. Amsterdam: De Bezige Bij.

- De Roo, B. Jos (2014). Praatjes voor de West: de Wereldomroep en de Antilliaanse en Surinaamse literatuur 1947-1958. Amsterdam: In de Knipscheer.

- Toppenberg, Alwin, Jules de Palm (1922 – 2013) | blog. [online] Werkgroepcaraibischeletteren.nl. Available at: <https://werkgroepcaraibischeletteren.nl/jules-de-palm-1922-2013/> [Accessed 30 May 2021].