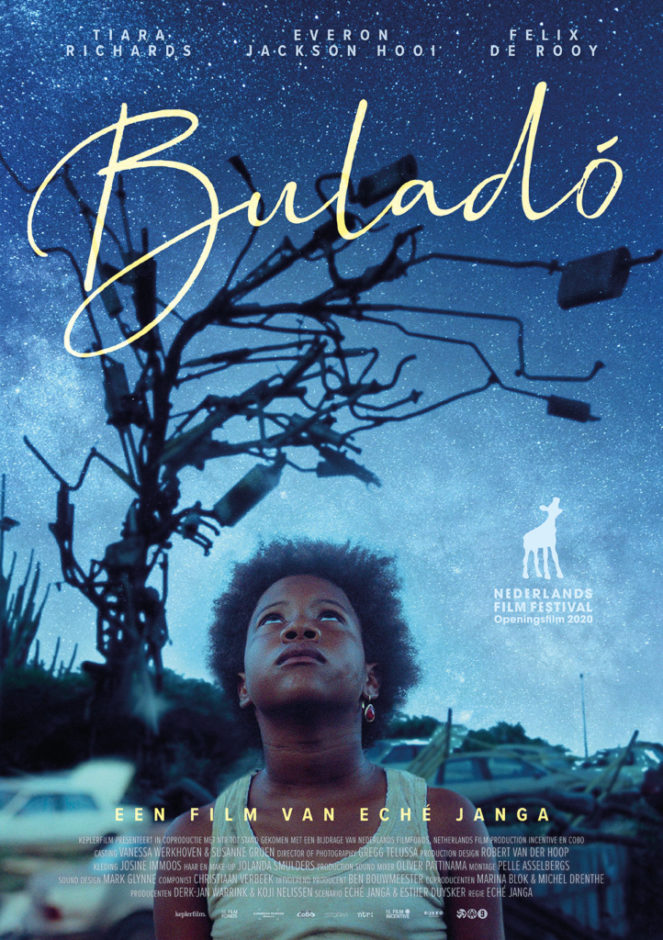

Buladó (2020) Dutch-Caribbean film representation

The friction between Curaçaoan orality and Dutch-Colonial ideologies of knowledge

by Radha Zievinger

Orality and indigenous knowledge systems have been- and continue to be- delegitimised by the global west due to their assumed incompatibility with how knowledge and facts can be shared, remembered, and enacted in every day life. This, combined with other factors, has led to the unfortunate lack of representation and artistic erasure of the rich oral traditions and creole language of Papiamentu. In this essay I will be looking at the Curaçaoan film Buladó (2020) from director Eché Janga in relation to orality and the field of Dutch-Caribbean film representations.

Specifically in regards to the title of the movie, the language used within the film, and the wider implications that this movie brings to the viewers attention relating to a Curaçaoan identity, the impact of colonisation, and the medium of film.

Buladó follows the conflict between two opposing approaches regarding Curaçaoan identity through the perspective of a young girl, Kenza. She lives with her father and maternal grandfather in the countryside of Curaçao. Her father, Ouira, represents and attempts to reinforce assimilation of Dutch culture by favouring the Dutch language over Papiamentu and his need for Kenza to learn through the Dutch education system. He constantly raises skepticism towards Kenza’s indigenous and spiritual grandfather, Weljo. Whereas Kenza’s grandfather reminds her of the great history, heritage, and spiritual nature of the island, her identity, and blood line through oral traditions. ‘Buladó’ as explained in an interview with the director Eché Janga, means ‘a flying person or thing’ (“Director Eché Janga” on Repeating Islands). Janga shares how the film and its title is partially inspired by an oral slave legend that has been passed through generations of his family, his own father being from Curaçao. The legend is about the slaves who worked on the salt pans in Curaçao holding onto hope through their belief that if they managed to flee the horrible conditions of the plantations they could jump off a cliff and fly back to Africa, freeing themselves from enslavement and inhuman treatment. Suicide is therefore represented through oral history as an empowering act, reclaiming the ownership of self from slave to individual, this is a concept that is well discussed by Paul Gilroy, “By robbing the slave master of the desired object of appropriation – the black body- the slaves inscribe their own agency.” (Gilroy 1993). Not only is Buladó based upon a specific and local oral history, the film itself reinforces the importance of orality whilst expanding the Dutch-Caribbean film portfolio in an important way, being in Papiamentu.

The language of the film is of great importance as Papiamentu is a creole language, representing the cultural identity and locality of Curaçaoans through their own vocabulary. This provides Papiamentu speaking islands and individuals with representation in grander media that is not often seen. It is unfortunately common that speakers of Creole languages face negative connotations regarding their ‘professionalism’ or ‘intellectualism’ due to classism as well as a preference to use ‘proper’ languages such as English, Spanish, Dutch, French in the ways that the global West does. Kenza’s father is shown only speaking in Dutch and consistently reinforcing the Dutch education system, raising skepticism and dismissing the knowledge and beliefs that Weljo introduces to her. Ouira’s attitude places more value on the Dutch colonial ideals of modernity and knowledge compared to the indigenous and cultural ways that his father in law and daughter feel connected to. Being in Papiamentu, the film reverses the common movie watching experience that Papiamentu speakers have, where they are othered whilst consuming media about themselves in Dutch or English, coloniser languages. Instead, they are able to access the true and unadulterated meaning of the language whilst othering those who cannot speak Papiamentu. The orality of Papiamentu is somewhat retained and meaning can be directly accessed by Papiamentu speakers without the mediation of writing, translation, or imitation. This brings the film a step closer to the traditional form of storytelling where, ‘Orality is attributed a certain supremacy as the storyteller symbolically assures the link with Africa…’ (Chinien 2014: 103). Buladó achieves a lessened distance from the traditional form of storytelling, and therefore orality, due to this lack of language barrier for the targeted audience of Curaçaoans, but does not completely bridge the gap due to the very nature of film production and of the Dutch-Caribbean film industry – or lack thereof.

Regarding the film production in the Dutch-Caribbean film industry, there remains the issue of privileged access to the knowledge, equipment, experience, and funding required to create a film of ‘industry standards’. As discussed in the lecture regarding Dutch-Caribbean film representations, there has been a limited focus and space allocated for schooling like film academies in the Dutch-Caribbean. In the past, this has been a main point of contention for local individuals aspiring to enter the film industry. Presently, there is a media school in Curaçao that provides short-term and hands on programs in many aspects of media production. This is already an improvement from the past yet it still is not the same level that would be acquired if met with the opportunity to go abroad. Regardless, it is a step in the right direction for the local industry and creatives on island. Janga touches upon the difficulty of filming in Curaçao in regards to the heat and the natural lighting but remarked that, ‘This was not a problem for the local crew members.’ (Repeating Islands). An important outward reinforcement that there is no lack of local enthusiasm or ability. It is also important for me to note that while Buladó is a captivating piece of Dutch-Caribbean film representation, it was also funded and produced from the Netherlands, highlighting the distance at production level from the island once more. This does not negate the importance of the film, the representation, or impact that it holds regarding the message of orality, heritage, language, and Dutch-Caribbean identity. It simply reinforces the space and potential for more control at every aspect of representation for the islands. The film already steps closer in equity regarding who directed the film, a Dutch-Caribbean individual with his own familial orality involved in every step of the process. This is particularly valuable and needed, especially when one thinks of films such as Tula: The Revolt (2013) which received a scathing review[1] in relation to insensitivity and the individuals who were in charge of the narrative regarding a key aspect of Curaçaoan heritage and cultural memory.

In conclusion, the film Buladó (2020) exposes the friction between oral tradition, cultural heritage, language, and the Curaçaoan identity in relation to Dutch ideologies of modernity imposed and reinforced through Dutch colonisation. The film also shows development in the manner of representation of Dutch-Caribbean films are produced, with the actors on screen being local and speaking Papiamentu as well as the director being of Curaçaoan decent. The way that orality is represented is one of the most exciting aspects of the film, it validates and claims the space that Papiamentu deserves in popular culture. It also clearly shows the fundamental role that Creole languages have in oral tradition regarding indigenous practices and connection to the the physicality of lands that have been too long refused to native populations.

Bibliography

Chinien, Savrina. “Memory of Trauma and Trauma of Memory in the Literary and Cinematographic Works of Patrick Chamoiseau.” Caribbeing: Comparing Caribbean Literatures and Cultures. Kristian Van Haesendonck and Theo D’haen. Amsterdam, New York: Rodopi, 2014. Print.

“Director Eché Janga: ‘My greatest wish was to make a film about the mystique of life.’” Repeating Islands, 3 Oct. 2020, https://repeatingislands.com/2020/10/03/director-eche-janga-my-greatest-wish-was-to-make-a-film-about-the-mystique-of-life/.

Gilroy, P., 1993. The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, p.63.

“Tula Will Decolonize Curaçao Cinematography.” Triunfo Di Sablika, 15 Aug. 2011, https://triunfodisablika.wordpress.com/2011/08/15/tula-will-decolonize-curacao-cinematography/.

Note

[1] By the Curaçaoan writer, poet, and working-class social critic Jermain Ostiana. “Tula Will Decolonize Curaçao Cinematography.” Triunfo Di Sablika, 15 Aug. 2011, https://triunfodisablika.wordpress.com/2011/08/15/tula-will-decolonize-curacao-cinematography/.

[Paper written for The Unknown Caribbean: Artistic key moments in Dutch-Caribbean history, UvA, 31/12/2021]

Radha Zievinger is a third-year bachelor student at the University of Amsterdam, studying English Literature and Cultural Analysis. She is highly interested in decolonial theory relating to the Caribbean in all regards. Born in Aruba, she is 20 years old but grew up moving between six different islands in the Caribbean. This has motivated her love for research and academic writing regarding the many facets that go into the complex idea of a Caribbean identity. She hopes to contribute to the growth of academic writing that places Caribbean individuals and experiences at the forefront of representation.

This is excellent work, Radha. I particularly applaud you for highlighting the dearth in access to funding capital for creative works that preserve and authentically represent culture and Caribbean indigenous peoples’ way of life, locally. Folklore is a key element in our Caribbean-ness. Notwithstanding, language barrier to wider audiences, it is important that we tell these stories with our own voices; uncensored and as told by own ancestors. So that context and flavour and integrity of the storytelling are preserved. Oftentimes, funding from external sources come with conditions that ultimately undermine and or disregard the cultural sensitivity required for this form of storytelling. I am happy that Bulado’s director was fortunate enough to have commanded such editorial and creative control over the process even-though funding for the film emanated from the “Motherland”.

On the subject of orality, the stigma spoken of in your piece is not unique to Papiamentu. Historically, Creole speaking was also discouraged and frowned upon by middle and upper socio-economic classes in Saint Lucia, Dominica and Martinique, etc (sorry I can’t provide academic references for this statement at the moment but it may be worth your looking into the tension between creole and the official languages in those islands mentioned).

I am happy to report though that I am aware of quite a number of recent and ongoing projects that seek to promote and preserve our creole and cultural heritage by repositioning their value proposition through film, literary works and other mediums.

Thanks again for sharing your work. Well structured and explained clearly. I am very proud to know you. Congrats on your progress and best wishes for continued success at university.

Cheers,

Onel Sanford-Belle